Guest Author: Jennifer Cochran Biederman

Editor: Patrick Cooney

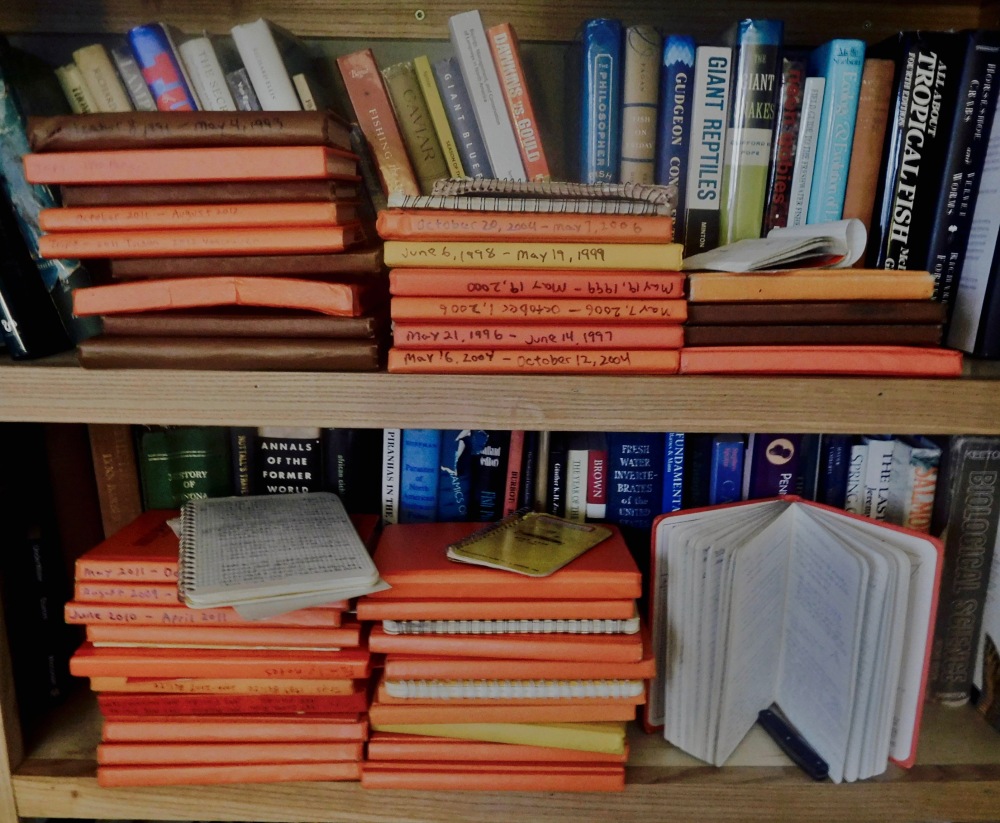

My father was a field biologist, fish professor, and natural historian down to his DNA. Most evenings, he’d make his way from the dinner table directly to his chair in the living room. It was his spot – surrounded by not-so-neatly arranged stacks of exams to grade, articles to read, and manuscripts to review. But always on the table beside him, sometimes wedged between the piles of papers, was a bright orange field notebook or two. After turning on a basketball game or, way back in the day, an episode of the Cosby Show, he’d slip on his reading glasses, and reach for the brightly colored book.

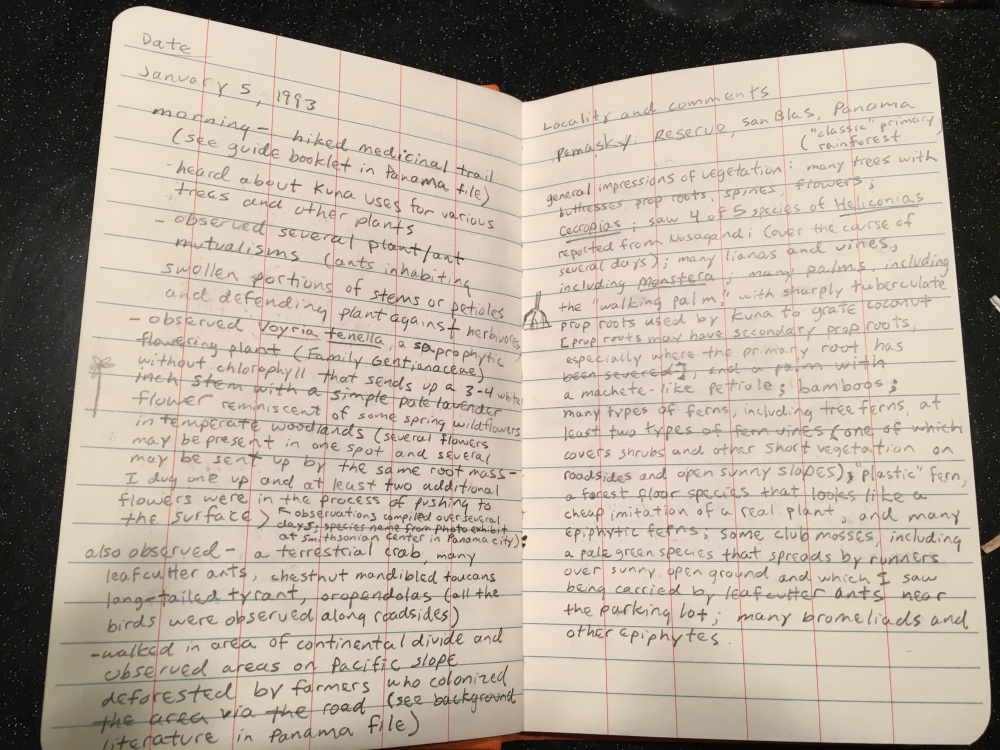

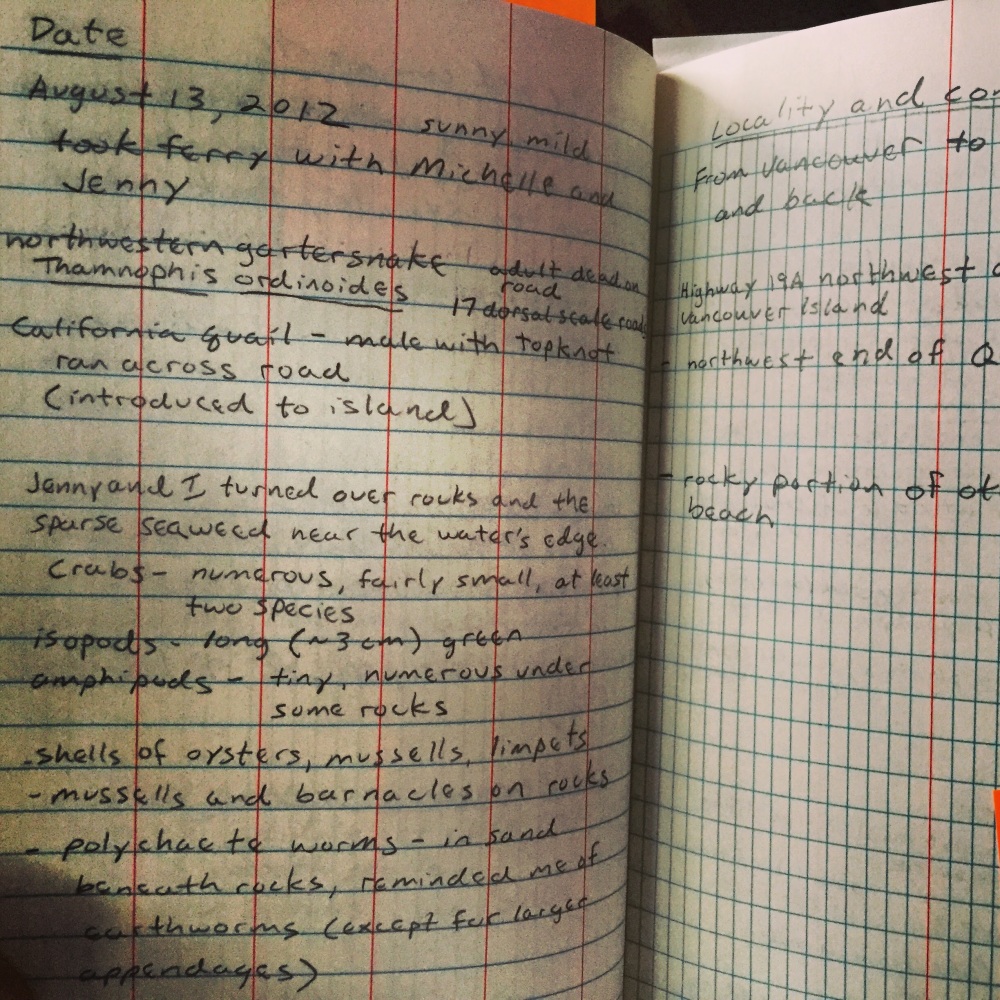

Inside the pages of a field notebook lies much more than raw measurements, species lists, weather patterns, sketches, and other notes that biologists tend to record during or after a day in the field. Collectively, these notes – although often patchy and sometimes perfunctory – capture a story that goes much deeper than what appears on a single page. In the case of my father, his collection of field notebooks – which numbered in the dozens and spanned his lifetime from age 8 until he passed away short of his 60th birthday – were the narrative of his journey as a biologist. And more.

I followed a similar professional path as my father and also became a field biologist. Unlike him, though, my practice of taking field notes has been far less than perfect over the years. My entries are often a bit scattered – certainly lacking the depth and, more importantly, consistency of my father’s. Early on as a graduate student, I recall feeling especially overwhelmed and exhausted at the end of long days in the field – and the thought of pulling out that notebook to record my observations – especially those that weren’t related to my work – felt like a bit of a burden. I assumed that a proper field notebook contained as much detail as possible – documenting all of the species (plants, fish, invertebrates, birds!) that I recognized and identifying those that I didn’t yet know. In an ideal world – this exhaustive approach is a great way to learn about biodiversity and natural history. But, not always realistic – especially for the graduate student balancing field work, a full-time teaching position, and motherhood.

It wasn’t until I paged through my father’s notebooks many years later when I realized that, although there’s a certain formula to follow, it’s best to focus on the elements that are meaningful to your own work and curiosities. Since then, I’ve evolved my own style and pattern – and actually look forward to the precious time I have with my notebook at the end of a field day. I’ve discovered that, over time, my interests naturally ebb and flow around different biota. In the spring, I’m especially eager to observe and record the first wild flowers as they bloom in the local forests. In summer, I’m more in tune to hatches of aquatic invertebrates – and take note as different taxa take flight from the stream behind my home.

Why do field notes matter for fisheries?

Recording field notes is a professional practice that seems mostly contained within the more personal day-to-day activities of the typical field biologist. In cursory conversations with fellow biologists, most of us were encouraged to develop these skills of observation and documentation – but as students, few of us were formally taught how. And, on a broad scale, it seems like the practice of keeping a field notebook is on the decline among younger career field biologists such as myself.

Why? In reality, we’ve entered an era of rapid technological advancement – and our field backpacks are as likely to contain an iPhone and laptop as it is a small brightly colored field notebook. To younger generations of field biologists-to-be, the act of writing in a notebook with a pencil might seem, well, a bit outdated and unfamiliar.

But by allowing this practice to slip away, what else might we lose?

1. Basic life history and ecological information

For starters – when it comes to fish, we need more basic life history information.

In the plenary session at the 2014 Joint Meetings of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists in Chattanooga, TN, former ASIH president Dr. William Matthews of the University of Oklahoma made a plea to students and early career biologists. Along with “taking good field notes” he urged for upcoming scientists to “publish everything you learn about basic biology or life history of any species.” Digging through several of the leading regional fish books (e.g. Fishes of Alabama, Inland Fishes of Mississippi, Fishes of Mexico), he found that a substantial proportion (up to 45%) of species descriptions contained statements like “Very little is known of the biology of this species.”

For those of us in careers where publications are encouraged and necessary for advancement, it’s no secret that natural history-related research (often observational) is far less celebrated than “sexier” studies utilizing tech-savvy methods or new theoretical ideas. However, the conservation of biodiversity depends on the former. As we tackle complex and intertwined ecological challenges including climate change, habitat loss and fragmentation, and even the potential dismantling and defunding of agencies such as the EPA, and protective policies such as the Clean Water and Endangered Species Acts, we need solid, baseline ecological information about vulnerable species in order to document changes and construct management plans.

Recording field notes as a habit is a way for field biologists to capture and record the basic ecological information that’s vital for protecting non-game fish – and other fauna – that may not benefit from the more focused and well-financed research aimed at other charismatic or economically-valued species. The key, though? To make these data valuable and accessible, seek to publish these observations whenever possible – even in small regional natural history journals.

2. The big picture

What’s more? As Dr. Matthews points out, chronicling your observations in field notebooks over the span of your entire career may provide you the opportunity to synthesize information in your field later on – piecing together many “small” observations into a longitudinal “big picture” of knowledge that’s incredibly valuable and publishable in the form of articles, chapters, and books.

3. Better field biologists

Lastly, many might argue that the practice of taking field notes is a critical piece of becoming a successful field biologist – nurturing keen observational skills, basic natural history knowledge, patience, and discipline. We live in a fantastically connected, fast-paced world where – even in the most remote of field locations – our work as field biologists can be derailed by satellite-delivered distractions like Twitter feeds and Facebook. I don’t discount the incredible value of sharing real-time tweets as we probe the natural world, but it’s important to know when to detach from this noise. Personally, the moments of discovery, growth, and inspiration that have shaped my identity as a scientist have been in solitude – with a notebook, pencil, and a field guide or two.

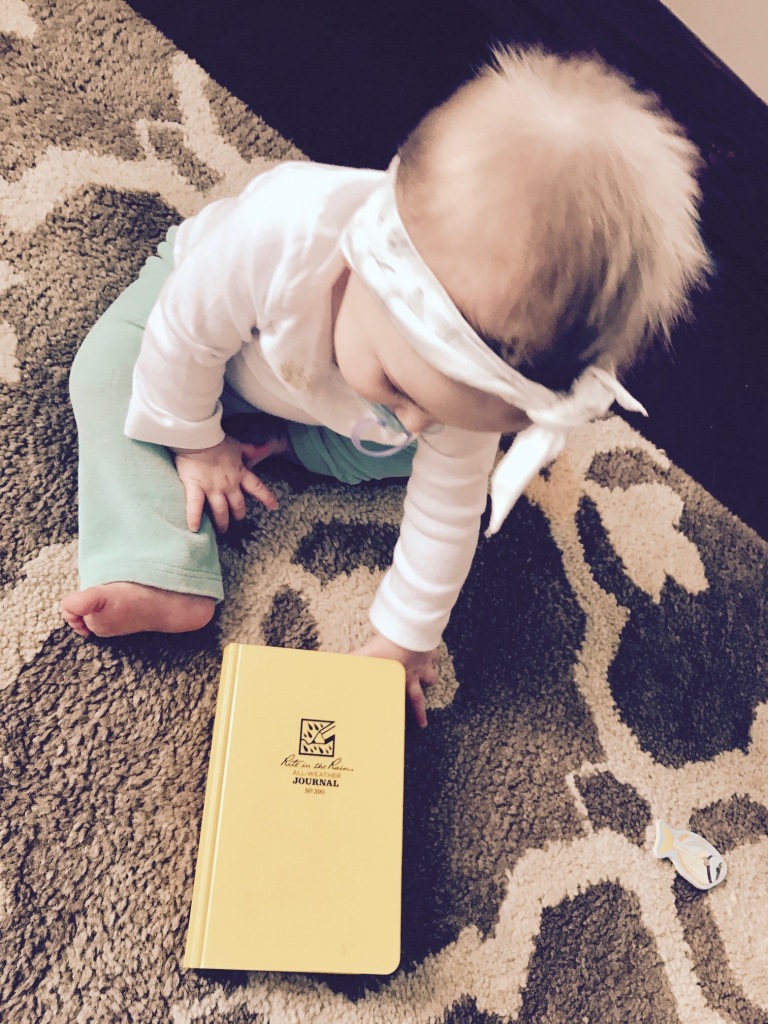

And, by the end of your career, you might find that your notes leave behind a little bit more.

Paging through my father’s field notebooks after he passed away, I discovered a deeply meaningful archive of memories. While he had used these pages to publish dozens of articles related to the natural history of fish, herpetological, and invertebrate fauna, here and there among the Latin names and GPS coordinates were brief notes that documented the happy days that my family had tagged along with my father in the field. Bookmarks in time – these passages are a gift and reminder that, for some, the duality of being a field scientist and parent/spouse/companion are best when intertwined.

When it comes to the future of field notes, I’m not sure how firmly this practice will be held among the next generation of field biologists. But I do believe that there is value in re-examining and reconsidering the impact it might have in shaping the way we gather, archive, and build knowledge about the natural world.

What is the role of the brightly colored field notebook in your life or career? As a student, scholar, scientist, or otherwise, do you have insight about the practice of taking field notes – as it relates to the past, present, or future? I’m very curious to learn about shifting trends in how this process is taught, valued, and practiced. Please leave a comment below and contact me with your thoughts and ideas – jbiederman@winona.edu

Literature cited:

Matthews, William J. 2015. Basic Biology, Good Field Notes, and Synthesizing across Your Career. Copeia (3): 495-501.

About the Author:

Jennifer Cochran Biederman is a faculty member in the Biology Department at Winona State University. She previously wrote about earning a PhD while having a young child. Three years later, and she is now the mother of three children. Her family has a trout stream running through their backyard, but she mentioned not having much time yet to fish with the little ones crawling around.

I appreciate this work, very well done, please continue. I also keep field notes, carefully, and since August 1983. I highly recommend it.