Guest Blogger: Meghan Fox

The following guest post was voted best in the class for an undergraduate assignment on fisheries management from Humboldt State University’s Fall 2017 Fish Conservation and Management course taught by Dr. Andre Buchheister. The assignment required students to find a peer-reviewed article on a fisheries management topic that interests them and to communicate the issue in a blog format to a general audience.

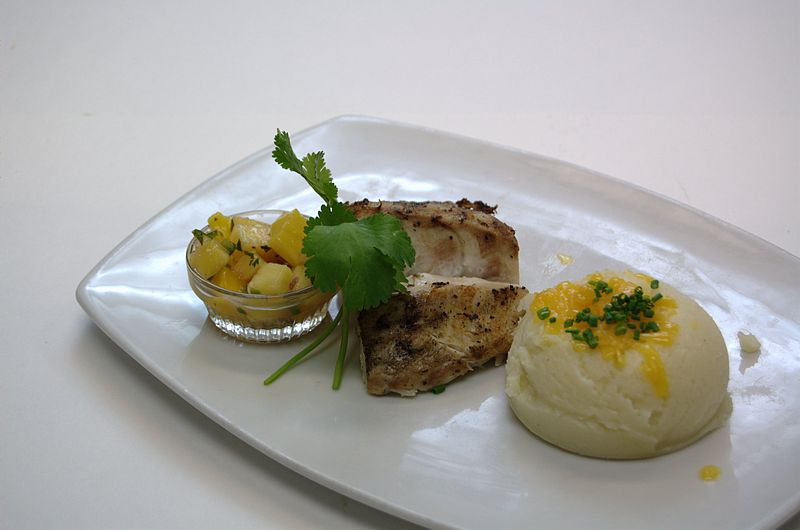

You order a plate of seared Mahi Mahi, and when the server arrives she puts in front of you a plate of lies. What you believe to be Mahi Mahi may really be a different species altogether, like Yellowtail. It is now very common for restaurants and food vendors to serve a fish that has been incorrectly labeled. If the mislabeling occurs at a restaurant or sushi bar, the vendors do it in a way that most people would not be able to tell the difference. However, DNA barcoding can be used by biologists or inspectors to identify exactly what species a product is, and results show how prevalent mislabeling really is. In 2010, Oceana conducted one of the largest seafood fraud investigations across the U.S. and showed that 74% of sushi bars, 38% of restaurants, and 18% of grocery stores in their sampling were selling fish that were mislabeled (Fisher, 2013). Another study by from the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) indicated that 40-50% of sushi samples from local markets and sushi bars were mislabeled each year (Willette et al., 2017).

Mislabeling can happen anywhere from the boat to the dinner plate. Mislabeling can be unintentional, such as misidentification on a boat if two species look similar (Willette et al, 2017). However, it can also be intentional, such as when a seafood retailer labels a cheaper fish as species that is more expensive, but visually similar, to increase profits (Jacquet and Pauly, 2008).

Consequences of mislabeling

Unfortunately, mislabeling is not only an inconvenience to consumers; it can lead to some serious health and environmental complications. The U.S. is the second largest seafood consumer worldwide and has experienced high levels of mislabeled fishes. In some cases, the fish that is being mislabeled contains higher levels of mercury than the fish it is labeled as. For example, Swordfish may get swapped for Mako Shark. Mercury can have negative effects on a person’s immune system, particularly a young child. That’s why pregnant women are advised against eating fish species that contain high mercury.

Misidentification and mislabeling can also affect estimates of fish stock sizes if it impacts the catch data reported to fisheries management personnel (Pepe et al, 2007). Mislabeling and misidentification at sea can contribute to the overfishing of different species, such as Yellowfin Tuna and Bigeye Tuna. When it’s harder to catch species like Bluefin Tuna, which are more expensive, a fish that has similar meat color and texture may be mislabeled as Bluefin Tuna, sending false data to fisheries managers, giving them an indication that the fishery for Bluefin Tuna is doing better than it really is.

On the other hand, mislabeling can sometimes be beneficial for fish populations. The UCLA study indicated that certain vulnerable species are often switched out for less vulnerable ones, like Sea Bream, which is classified on the Seafood Watch list of “least” of concern for Red Snapper (Willette et al, 2017). A lot of times, some species of lesser value that may not have a large market are being purposely mislabeled as other, more popular species. By selling these lower value species, some fisheries or fish retailers have secretly been creating a new market for the lower value species which may lessen the pressure on the higher value (and typically overfished) species for which they are swapped (Jacquet and Pauly, 2008).

Addressing mislabeled fish

Given the extent of the mislabeling problem, policy and protocol changes are starting to be enacted. Fisheries management personnel have begun the first steps to inspecting commercial fish more. One of the ways they have begun looking closer is by using DNA fingerprinting and making a database that includes many different fish species. Additionally, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations recommends to include the actual site where fish were captured in labeling, which can flag a potentially misidentified fish if it is caught in an area where the species isn’t typically found (Jacquet and Pauly, 2008).

Consumers can also make a difference. Consider asking questions such as:

- What species of fish am I ordering?

- Is it wild or farmed?

- How was it caught?

- Is the price too good to be true?

Often, answering these questions can help identify a potentially mislabeled product. It is rare for a whole fish to get mislabeled, so when possible, try to purchase a whole fish (Fisher, 2013). And of course, one fool proof way to ensure you don’t get served a plate of lies is to venture out on your own and catch your fish yourself… just make sure you can properly ID what you caught!

About the author

My name is Meghan Fox and I am currently a freshman at Humboldt State University majoring in Fisheries Biology (with an emphasis on marine fisheries). I look forward to possible volunteer/internships that are ahead that deal with fishes in the ocean. My dream job would be tracking the breeding and migration patterns of pelagic species of fish.

I developed a connection with the ocean by living in the coastal town of Morro Bay and going to the beach from the time I could walk. I’ve always felt like I needed to do my part and help the ocean in some way. When I was old enough, my dad started taking me out on the party boats to go fishing and that’s where I became hooked on being out at sea. I got my first job at the age of 14 working the decks of these fishing boats and this influenced my decision to study Fisheries Biology in college. From what I hear, it sounds like my major is a little challenging because of the hard work, but I’m ready to do my part and help the ocean with the knowledge that I receive from my major.

Bibliography

Fisher, E. 2013. Oceana Study Reveals Seafood Fraud Nationwide. Oceana USA.

Jacquet, J., D, Pauly. 2008. Trade secrets: Renaming and mislabeling of seafood. Marine Policy 32: 309-318.

Pepe, T., M. Trotta, I. Di Marco, A. Anastasio, J. M. Bautista, M. L. Cortesi. 2007. Fish Species Identification in Surimi-Based Products. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 55: 3681-3685.

Willette, D., S. Simmonds, S. Cheng, S. Esteves, T. Kane, H. Nuetzel, N. Pilaud, R. Rachmawati, P. Barber. 2017. Using DNA Barcoding to Track Seafod Mislabeling in Los Angeles Restaurants. Conservation Biology 31: 1076-85.

For other Humboldt State student posts, please see:

- DANANANANANANANA BAT RAY by Angela Schmidt

- FROM REEF BANK TO FISH TANK: HOW THE AQUARIUM TRADE CAN IMPACT CORAL REEF CONSERVATION by Josh Cahill

- THE PEACEFUL BETTA by Joelle Montes

Nice job, Meghan! Here in the South Pacific island region, there is another concern: ciguatera. Mislabelled fish can end up causing direct harm, not just the slow build-up of mercury. Sometimes restaurants serve an alternative fish simply because they ran out or don’t have access to the fish on the menu that day, but there should be an option for the restaurant to share that information with the consumer without embarrassment or fear that the customer will leave in a fit. Something we can all work on together: customers, service sector and fisheries community!

Hi Tiffany, I agree with you on how restaurants should at least notify their customers if they have run out of a specific fish and have a replacement for it. It would give the customer a sense of trust that the restaurant would notify them before serving something different.

Thank you, Meghan Fox

Meghan, what an incredibly small world. I was a CDFW sampler on several of the party boats out of Morro Bay and totally remember you helping out. I am so glad that someone so passionate about the ocean is pursuing a degree in fisheries. Seafood traceability is such an important component to sustainability. Great Blog!!

Hello Oliviya, I find it very cool that my article got to you and that you remembered me from the boats. I’m glad you liked my article.