As told by Duane Raver and created by Patrick Cooney

One of Duane Raver’s pieces of art is arguably the most viewed piece of fish art ever made. For that story, be sure to read the footnote at the end.

I really don’t remember the first fish I caught, maybe a bluegill or a pumpkinseed sunfish from an Iowa creek or farm pond when I was maybe six or so years old in the Dust Bowl days of Iowa. Flash forward to my final fish some eighty plus years later. It likely was a crappie from a pond near our Johnston County, North Carolina home.

If you can stand it, here is an accounting of some of the events (and fish) that occurred in between catching my first and last fish.

Early life

Newton, Iowa has at least two distinctions: it is the town where The Maytag Appliance Co. got its start and it is where I, Duane Raver, Junior, was born.

My mother used to say that my birth was about two weeks after Lindbergh landed the Spirit of St. Louis in Paris, France. So, you historians can calculate how old I am now.

Fish and fishing have always come naturally for me with parents and friends from my early years showing me angling skills. I can still remember the first cane pole I used in the Dust Bowl ridden years of the 1930s all the way to the long-used 1948 split bamboo flyrod and Pflueger Supreme casting reel I received as a 21st birthday present.

The Inspiration

The first urges to draw and paint fish are lost in my hazy recollections, but dates of 1940 are penciled on many of my attempts at picturing fresh-caught fish flopped on the kitchen table. Even in those early days of trying to develop drawing and painting techniques by observing skilled artists of the day, it was pretty much trial and error for me (and still is!).

I could list a dozen or more artists from the 1940s and 1950s that I admired, but few were “fish specialists.” Then the name of an Iowa artist, Maynard Reese, caught my eye. My worn copy of “Iowa Fish and Fishing” dated 1951, (which I regret that Maynard never signed) with his lovely fish art, was a real inspiration for me.

Over the years many excellent fish illustrators (and even some not so good) have come and gone. Top-notch folks I admired over the years include Florida’s Wallace Hughes and Diane Peebles, national Geographic’s Walter Weber, Pennsylvania’s Ned Smith and currently on top of the list, Joe Tomelieri, whom no one will ever surpass.

College Years

It was evident early on that the Good Lord had given me a measure of artistic ability and that I loved fish science. As the mid 1940s hit, I had to make the decision of college or art school. The pull of fishery biology at nearby Iowa State College (now University) won out. While fishery biology was my main focus, I had a job as a mailman, and also played sousaphone in the Marching Band and was involved in the laboratory experiment club.

While in college I spent two summers employed as an assistant fishery biologist with the Iowa Conservation Commission stationed at Spirit Lake, Iowa. This hands-on practical experience of netting and handling fish would prove valuable later on.

Despite going to school for fishery biology and working in the summers, I always made sure I had time for drawing and painting on a “self-taught” basis throughout college. On the weekend afternoons I took the opportunity of sketching various local fish at the hatchery’s large aquarium. I still have some of those stained drawings and paintings dated “Spirit Lake 1944.” I even made my first “sale” of any of my artwork for a whopping $5.00 for a sketch I did for the “Fin and Feather News” of Lufkin, Texas.

Those summers were not without a couple of “adventures.” In fact, one was a particularly foolish adventure. Four of us set out in the little wooden johnboat with its struggling 5 horsepower Johnson outboard. The wind came up and swamped our craft and the hip waders we were wearing, leaving us treading water in the middle of Lost Island Lake. Luckily, people in a larger boat saw our calamity and rescued us. “How deep was the water,” my rescuer asked. “I didn’t go down to find out,” I replied in a panting voice. And thus began a greater appreciation for boater safety!

After graduating from Iowa State College in 1949 and taking up local fishery work, the northern Iowa weather turned from fall to winter and with it came below zero temperatures. Working outside in the biting wind off Spirit Lake while tagging fish seined by the hardy “roughfish” crew from cuts in the thick ice was enough for me to know that a change of scenery was needed.

My faithful 1948 Ford knew the way to my hometown of Ames. Now what? A degree in fishery biology, but no job prospects. I changed course and enrolled at the University of Iowa in, of all things, “Museum Technics”! Actually, the Iowa folks were more interested in what they had learned of my fledgling art ability and they needed designers for their exhibit backgrounds.

Career Beginnings in “The Promised Land”

But then fate stepped in. I got a phone call from an Iowa State classmate of mine. He was leaving his job with the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission and he wondered if I would like his Job as a fishery biologist! “But they don’t know a thing about me,” I tried to tell him. “Oh, they know that you were a student of Dr. Ken Carlander, and that’s enough for them,” he said. Talk about associating with the right people at the right time! And I said yes (or I wouldn’t be writing this). I had less than a week to arrive on the job since my classmate was leaving February 5th, 1950.

Let’s see now. Raleigh, North Carolina is where I want to end up. No interstates back then, some late winter high water on the roads, and a road map at best. I packed my pearl gray ’48 Ford and hoped, “She better not fail me now.” And she didn’t. February 5th, 1950 or so, I drove into downtown Raleigh past a guy mowing grass at the First Baptist Church with an antique push lawn mower. Mowing the grass in February! After freezing Iowa weather! This was the promised land indeed!

I met my new boss, J. Harry Cornell, Fish Division Chief. He had been on the job only a couple of weeks when I came on. Actually, the Wildlife Resources Commission as an agency had been in existence only two or three years. Clyde Patton, Executive Director, had proceeded us by a short year or two.

Now what do we do? An ex college professor (Cornell), a green fishery biologist (me), and an infant organization that some folks liked, and some didn’t. What had I gotten myself into? I figured I would just try to appear that I knew more than I did and hope for the best.

I was shown my desk in the basement of the State Education Building. My desk! It was right beside that of a fair-haired lad who looked as if he was right out of high school. And on the other side was a few-words guy that looked all business. The lad turned out to be Garland Avent (yes, the future dad of expert gardener, Tony Avent). The laid-back fellow was Dave Nolan, Commission engineer.

We all struck if off just fine. They both accepted me, “The Yankee”, very quickly. Garland shuffled papers and Dave looked after the Commission’s fish hatcheries and an obsolete game farm, and so forth.

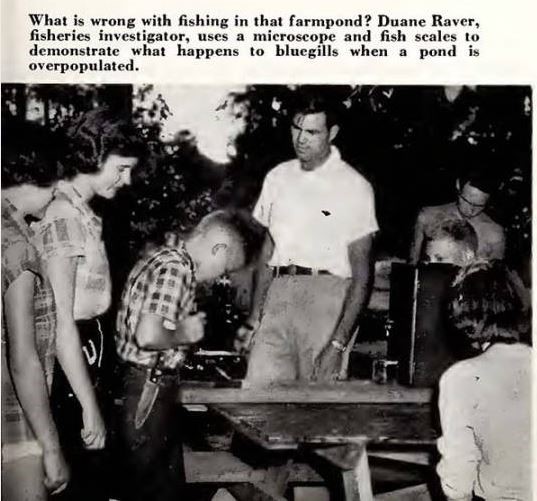

And me? I was handed a box full of a hundred or so fish scale envelopes. I was to read the dried scales and determine the age of the fish that they came from. Somehow my experience with age and growth of fish had preceded me from Iowa State. Mistake number one: “Where is the fish scale projector?” I inquired. “The what?” was the reply. Fortunately, an adequate binocular microscope served quite well, and I set to work. So far so good, I thought.

Days later Harry handed me a list of a dozen lakes and reservoirs that had not been surveyed, or studied recently, or probably, never. I was told to go to N.C. State College and pick out three of their best wildlife students to work with me on the surveys. Harry said that Dr. Fred Barkalow would help with this selection. They would be my “crew” for the formidable summer task. F. Eugene Hester, Don Baker, and Frank Richardson were selected.

Little did they know (nor me) what awaited us. I did what I could to locate gear we might need: a 12-foot Model E Alumacraft boat (it looked like it hadn’t been used in years), a 10 horsepower Mercury outboard (would it even start?), a few usable nets, and a musty old Higgins camper that would be used as the crew’s sleeping quarters (while I slept in nearby hotels!). Yet with all these uncertainties, I heard few grumblings. They all worked out well and all went on to bigger and better careers—in spite of their “first boss.”

The work we conducted in the early 1950’s laid a lot of ground work for understanding the aquatic systems of North Carolina and the fish that could be found throughout. All the credit goes to the hard working fellas out there every day.

The following spring it seemed like the construction of farm ponds was everywhere statewide. Almost each one came up with various fish management problems that had to be looked after. Although the U.S. Soil Conservation Service took care of the construction of these ponds in those days, it was the Wildlife Commission’s responsibility to assist with pond management.

We soon hired a couple of biologists and eventually went to the present system of nine Wildlife Districts, each with its own personnel. We were blessed with a bunch of good biologists in those early Fish Division days. Some had to handle everything from temperamental trout problems to those farm ponds to experimental reservoir trials as they came along. We even got to try out newly developed field gear as it became available.

The People, Places, and Projects

As we hired new biologists, I became responsible for the supervision of many of them. Handling personnel was never one of my better achievements. Take for example that rainy night about 10 p.m. when a knock on a western North Carolina motel door rang sharply. In bounced a newly hired biologist from Southern Illinois University. He was wearing a Ruger six-shooter pistol and he handed me a business card, as if he were “Paladin”, the Richard Boone television character. The card read “Have Gun – Will Travel; Darrell Louder.”

Darrell did excellent work on fish and I had the opportunity of doing some artwork for the science that he published.

Not only was Darrell an excellent biologist, but a herpetologist of far reaching skills. So far-reaching that he eventually had a “pet” alligator of some proportions in his city limits backyard. The town (no names please) posted an ordinance forbidding keeping alligators in town limits. Sorry to single out this and other numerous exploits of this well-meaning adventurer, but Darrell was tough to tone down.

Perhaps my inability to “tame” the biologists that I supervised somehow gave them enough space to become leaders in their own right. Darrell left North Carolina’s Wildlife Resources Commission to become Executive Director of Delaware’s Division of Fish and Wildlife. By the way, he took his Ruger pistol, his 12-foot boa constrictor, and his alligator with him.

Then there were fish hatchery situations that needed attention and Harry Cornell and I worked in visits to them. One hatchery superintendent was reminded not to shoot ospreys when I found a loaded shotgun leaning in a corner of his office on one visit.

Some other projects required a bit of new thinking and procedures. We knew of the Weldon fish hatchery that had been used by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for years to produce striped bass fry. The Roanoke River at the hatchery’s doorstep had spawning runs of “rockfish” as the searun striped bass were known locally.

It was late winter, and the Roanoke would soon be filled with spawning searun stripers. Time to check out Weldon hatchery. I met John Asbell of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service at the hatchery (this was actually a federal agency property ) one early spring day to look over the aging wooden structure.

We opened the creaking door and I noticed that the floorboards had an inch or so space between each of them. “What is with these spaces?” I asked John. “Oh, that’s to let the water out,” was his reply. To let the water out, I thought. What water? John pointed over to one wall. There were two highwater marks maybe a couple of feet from the floor. “That one was from the spring of 1939 and the higher one from 1943,” John said. To let the water out!

The dam for Kerr Reservoir was being constructed at the time and was yet to harness the Roanoke River on its spring floods that often swamped the helpless hatchery.

We weren’t looking forward to any highwater prospects, but we fixed things up a bit and proceeded with hatchery operations. We had a lot to learn in a hurry!

Twenty or so large, tall hatching jars were found and lined up on sturdy platforms. City water furnished by the town of Weldon was piped into a large elevated tank right outside the building. Unfortunately, the float valve stuck now and then letting the overflow cascade before we could shut it off. It woke me up several times the next month or so.

Now for “ripe” eggs and milt to fertilize the eggs. These came from local hardy fishermen who ventured out onto the Roanoke River, spotting “rockfish fights”, gathering of large female stripers and eager much smaller male fish in their spawning rituals.

The fishermen positioned their boats very near the “fights” and used large, long-handled dip nets to capture the amorous fish. Sometimes it worked, but often it did not. With any luck, the fisherman would bring us a 15 to 30-pound female and a couple of the much smaller “bucks”. This happened at all hours of the night at the height of the spawning season. Little sleep did we get.

A big fish yielded thousands of eggs that were extracted from the fish and fertilized. The Wildlife Commission paid the successful fisherman so much per estimated number of eggs. And he still took the fresh fish home!

All went well. Well, not quite! One dawn morning I emerged from the hatchery’s tiny “bedroom” to look over the jars full of swirling eggs. I must have blinked when I saw, not glassy live eggs, but tapioca-white all dead eggs. Remember, the town of Weldon supplied its water to our operations. That night the water department had added a water purification chemical to the water supply. Every egg in the row of jars, dead! Better luck from now on. And it generally was quite successful with tiny striped bass fry stocked in suitable North Carolina lakes and reservoirs.

The state of New York wanted to introduce striped bass to some of their inland waters and we wanted walleye eggs for trial hatching and stocking a few of our cold-water lakes and reservoirs. A trade was worked out and we were notified that walleye eggs were on their way from New York State. Harry and I drove to the then tiny Raleigh-Durham airport. No security, just a wave to pull up to the taxiing Eastern Airlines DC-3 plane and unload a couple of sloshing milk cans of walleye eggs.

Table Rock Fish Hatchery near Morganton, North Carolina did the rest and walleye fry soon were ready for stocking. But introducing this species to places where it had not previously existed was another story of some success and some not so good.

Keeping the fairly new Fish Division rolling smoothly began to work out with new biologists added and increasing knowledge of the vast inland waters of the state. Office work and field work blended as time went on, and we developed effective ways to properly relay to anglers and law makers the scientific information that we were collecting.

In the mid 1950s, an interesting assignment for me popped up. Harry Cornell, almost casually one day, asked if I would take Governor Luther Hodges fishing! I do not recall my exact reaction, but it was bound to have been one of complete surprise. As it turned out, the Governor was an avid angler, trout fishing with the likes of other prominent North Carolinians, like Hugh Morton (conservationist who preserved Grandfather Mountain, the highest peak in North America East of the Mississippi River).

It was late March and Harry said to try Bass Lake where he lived and had his boat ready to go. No security, no Highway Patrol, no bodyguards, Just Hodges and me! The fishing day was quite mild for late March as we loaded the Alumacraft and sculled- it was one of those push-pull devises on the stern of the boat- across the calm lake. A strike or two but no fish.

You know how North Carolina weather can change in late spring. Well, mid-morning it did. A chilly wind and white caps. It was all I could do to push the boat to shore. The day’s end? Nope, Hodges wanted a fish! Long story short, I knew of a nearby sheltered pond. Miracles of Miracles, the Governor caught a keeper bass as we cast from the pond’s dam. “Come and help us eat it tonight,” Hodges offered. But I made up some sort of excuse and declined. Thinking back on the brief encounter, it could have had a much different ending. I was glad that the following days were more routine.

Artist, Scientist, Educator, Editor: Many Hats to Wear

Among the many projects that occurred dating from my early days at the Wildlife Commission and the date of my retirement, there were requests from schools and state agencies for our assistance. One of these requests came from N.C. State (in 1950 the college had not become a university). They wanted a Fishing School! Actually, two fishing schools, one featuring freshwater angling and later, one learning saltwater ways. I got the nod to attend the freshwater one at Fontana Reservoir and act like I was an expert in fish biology and “how to” fishing. Far from it.

Then when the Saltwater version was added and located out of Morehead City, N.C., I had to soon admit that I wasn’t much of a “deep sea” goer. I remained as a “school representative” but tried to beg off of the offshore trips. Dr. Bill Hassler headed up these weeklong summertime schools, some of which were trips to the blue waters of the gulf stream. I have long since lost track of the evets and don’t know if they are still offered.

Then came the Federal Aid to Fisheries program, the Dingell-Johnson Act. It was similar to the game act, the Pitman-Robertson program that was quite a success. In 1956 I was given the responsibility as Dingell-Johnson Federal Aid Coordinator.

If it were not for help from P-R Coordinator Stuart Critcher, and his patient secretary Lorraine Thomas, I would have been completely lost in Federal Government rules and regulations. But it really was not my thing and after time and frequent comments from Director Patton, I was happy to relinquish the position to Bob Stephens, and ultimately, to Fred Fish.

Becoming a Professional Artist

In the meantime, quite early in my Fish Division career, “they” discovered that I had some wildlife art and writing abilities. While working as a Fish Investigator and as Federal Aid Coordinator, I provided some sketches for pamphlets and educational materials, and contributed some articles to the newly created North Carolina Wildlife Magazine.

After multiple illustrations that accompanied articles, they asked if I would be interested in doing a cover painting for “Wildlife in North Carolina” magazine. I was not too sure that the Commission’s artist at that time, Win Donat (pronounced Dough-Nay), was too thrilled about my treading on his turf. But I did the painting as best as I could anyway.

It was in the September 1954 issue, and I think it was a walleye. This opened a bit of a door.

“How about another painting–maybe an article or two on fish or fishing?” they asked. The door opened wider and if you have followed “Wildlife in North Carolina” magazine since those early days, you may know that I was fortunate to create more than hundred or so cover paintings, along with assorted fish book illustrations, angling articles, and poster illustrations. During this time, other states also commissioned me to create illustrations for their magazines.

Considering the articles and the illustrations I was making, there became an obvious consideration of my switching from the Fish Division to what was then the Education Division. Rod Amundson, Division Chief at the time, knew that I was better suited to work in education rather than as the Federal Aid Coordinator. He said to “come on over,” and the transfer was made in November of 1959.

The Division staff at that time was rather limited so we all had to wear several hats. Which is still true today. Work with school groups, both in classrooms and field trips, wildlife club talks, a film on fish and fishing, which was sometimes “weakly”, TV programs, news releases, and, of course, the then monthly magazine. It was this publication that more and more became pretty much my design and layout (no computers or graphic electronics to punch).

Those old days of cut and paste, measure the photographs, run it all down to Graphic Press in time for press time seems so long ago. Fifty cents was the annual subscription price for many years. Yes, fifty cents PER YEAR for all 12 issues! It wasn’t until the late 1960’s that we had to increase the rate from fifty cents to one dollar for the year.

Color on not just the cover, but also the inside, was a welcome innovation.

Jim Dean came aboard and then David Williams. What outstanding contributions they both made to the magazine and to our entire program. And a big relief to me.

Over the years, I was able to contribute artwork for the Wildlife in North Carolina magazine .

I was also able to contribute to the Virginia Wildlife magazine, Pennsylvania Angler, and many others.

I was also fortunate to represent the North Carolina Wildlife Commission in supporting youth programs.

Twenty years went by swiftly, and hopefully, they were mostly effective.

Retirement

There came a time when I needed to leave things in good hands and fade away from the day to day responsibilities for the magazine. Free-lance wildlife artwork beckoned and in June of 1978 I retired from the agency that had done so much for me.

Did we really part ways? Almost! Really, I just switched jobs-again. I was, and still am, grateful for opportunities to help with artwork from time to time for the Commission.

Years before “retirement”, I had watched a lady artist with the N.C. State Fair Village of Yesteryear work her magic in the old, drafty building near the new, round Holshouser building. I thought maybe I could do something similar someday. In the summer of 1978 a call to the Fair folks, and eventually the Village director, Mary Cornwell, brought a quick surprise. “Come on to the Village in October,” she commanded. You did not argue with Miss Mary. I really hadn’t prepared much art for display, but I went that first year, and “demonstrated” painting odds and ends during the then week long Fair.

My time at the Village of Yesteryear at the North Carolina State Fair turned into 36 years of 12-hour days at the Village. Father Time ultimately told me to quit, and we have come back to the Fair for only a day or two each year. Time will tell how much longer I can continue even this much each October! It was a good run-meeting generation of Fair goers—local, state, and international visitors. I saw kids that watched me painting fish, squirrels, birds. Some of the youngsters came back to the Village of Yesteryear long after they had children of their own.

When Life Becomes Art

Then, out of the blue, Chuck Manooch (Dr. Manooch, please) came to me with an offer to illustrate a fish book he was considering writing—but only if I would do the 150 salt and fresh water fish paintings. Why not! No time limit, but I began the work very soon after we made the deal. Wayne Starnes, then with the State Museum of Natural Sciences, furnished countless preserved fish specimens and I dug out my old field sketches from the 1940’s as a reference to my new illustrations. Publication date was the spring of 1984. The book did so well that we did three printings after that!

The completed illustrations have been, and still are, being used many places. Over the years, I illustrated many books, but this one is by far the most extensive and rewarding. I am so glad that I said yes to Chuck at that time in my lief. Such detailed art projects are pretty much out of my reach now.

The time has come to seriously examine my brushwork. It never has completely satisfied me over the years and the brushes are now cooperating less and less. I have moved my studio out of our daughter Diane’s taxidermy shop and set up a much smaller version in a room in our nearby Johnston County, North Carolina home.

I am fortunate to be able to work at all at 93 plus years old. How many fish scales and bird feathers have I painted on paper, wood, fabric, and canvas since those first attempts? But as Lunette Barber, a long-time excellent educator with the Wildlife Commission, said many times in her declining years, “You can’t win against Father Time and Mother Nature”.

Now my hand-crafted flyrod, a gift from a friend many years ago, stands in a safe corner of our garage wistfully waiting for just one more cast and one more tugging fish. I have all my family and generations of kind friends to thank for all their encouragement these many years. Not all of these years have been as productive as I should have made them. So just remember: Old fish biologists never die, they just smell that way.

About Duane Raver

By Patrick Cooney

The above account is Duane Raver’s own recollection of his life in Iowa and his career in North Carolina. Duane is a very humble individual, and during his telling of the above account, left many of his personal accolades out of his own account. I know it is not that he forgot about the many accolades he has earned…it is that he is one of the world’s nicest people, and after 93 years, has no need to boast about a career of service and dedication to fish science and art.

Considering the extensiveness of this article, it is only logical that we fill in a few gaps in Duane’s story so that we can capture all of this information in one spot.

I met Duane in the late summer of 2005 at the North Carolina State Fair. I was walking with my wife through the Village of Yesteryear (described by Duane above), and I saw a man painting these incredibly familiar illustrations of fish onto hand carved paddles. In fact, they looked exactly like the illustrations of fish that I had on a poster hanging on my wall back at the house. Sure enough, the artist was Duane Raver, and there he was sitting right in front of me. My wife and I promptly purchased some artwork…two hand carved paddles, one with a smallmouth bass painted on it, and the other with a redbreast sunfish.

Fast forward to today, and I have more than 30 pieces of Duane’s original art hanging on my walls at home and in my office. When I lived in North Carolina, I would occasionally take my lunch to Duane’s art cabin and sit with him and listen to him tell stories while I ate and he painted. These days, with an entire country between us, I am now relegated to picking up the phone and dialing him when a conversation is to be had. Duane still remembers people’s names, years of events, and details of happenings like no other.

During Duane’s career, he was named North Carolina’s Wildlife Federation’s Artist of the Year 4 different times. Duane’s artwork was utilized as License stamps for multiple years. He was awarded the highest civilian honor to a North Carolina citizen when presented with The Order of the Longleaf Pine. And he was honored by his fisheries colleagues with the Fred Harris Conservation Award.

To demonstrate how humble Duane Raver really is, it is important to demonstrate the only flaw in an illustration that he has pointed out to me that I can actually confirm is real. He will try to point out an extra fin ray here or there even when the illustration depicts the number of fin rays that are well within the scientifically accurate range for the species. I must say, that yes, there is one flaw that Duane brought to my attention over the years that has been real. It is a turkey illustration for the front cover of Wildlife in North Carolina from April 1972 that still haunts him to this day.

A month later, Duane received a letter regarding the lack of spurs on the male gobbler. To this day, because of how detail oriented and true to the scientific accuracy of his subjects, Duane uses this example to remind himself each time he paints to insure that every detail is accurate.

I thank Duane Raver for inspiring generations of scientists, artists, and anglers alike.

The Most Viewed Piece of Fish Artwork Ever?

I have to believe that Duane Raver’s painting of a Striped Bass is the most viewed piece of fish artwork ever.

Two billboards, one facing either direction, are viewed on Interstate 95 in the State of South Carolina as you drive across the Santee Cooper River (impounded as Marion Lake).

An average of 36,600 vehicles per day drive over this bridge, for a total of 13,359,000 cars per year. The fact that most of the cars that go by are carrying multiple people, there is a billboard facing in both directions, and the billboards have been up for decades, gives me the impression that this artwork has been viewed hundreds of millions of times! There aren’t too many pieces of fish art in the world that can boast that kind of exposure.